Visigoths

The Visigoths first settled in southern Gaul as foederati to the Romans, a relationship that was established in 418. However, they soon fell out with their Roman hosts (for reasons that are now obscure) and established their own kingdom with its capital at Toulouse. They next extended their authority into Hispania at the expense of the Suebi and Vandals.

During their governance of Hispania, the Visigoths built several churches that survived, and left many artifacts which have been discovered in increasing numbers by archaeologists in recent years. The Treasure of Guarrazar of votive crowns and crosses are the most spectacular. In 507, however, their rule in Gaul was ended by the Franks under Clovis I (45th great-grandfather), who defeated them in the Battle of Vouillé (killing Alaric II in hand-to-hand combat). After that, the Visigoth kingdom was limited to Hispania, and they never again held territory north of the Pyrenees other than Septimania, where an elite group of Visigoths came to dominate governance, particularly in the Byzantine province of Spania and the Kingdom of the Suebi.

In or around 589, the Visigoths under Reccared I converted from Arianism to Nicene Christianity, gradually adopting the culture of their Hispano-Roman subjects. Their legal code, the Visigothic Code (completed in 654), abolished the longstanding practice of applying different laws for Romans and Visigoths. Once legal distinctions were no longer being made between Romani and Gothi, they became known collectively as Hispani.

In the century that followed, the region was dominated by the Councils of Toledo and the episcopacy, and little else is known about the Visigoths' history. In 711, an invading force of Arabs and Berbers defeated the Visigoths in the Battle of Guadalete. The Visigoth king, Roderic, and many members of their governing elite were killed, and their kingdom rapidly collapsed. This was followed by the subsequent formation of the Kingdom of Asturias in northern Spain and the beginning of the Reconquista by Christian troops under Pelagius.

They founded the only new cities in western Europe from the fall of the Western half of the Roman Empire until the rise of the Carolingian dynasty. Many Visigothic names are still in use in modern Spanish and Portuguese languages. Their most notable legacy, however, was the Visigothic Code, which served, among other things, as the basis for court procedure in most of Christian Iberia until the Late Middle Ages, centuries after the demise of the kingdom.

Nomenclature: Vesi, Tervingi, Visigoths

The Visigoths were never called Visigoths, only Goths, until Cassiodorus used the term, when referring to their loss against Clovis I in 507. Cassiodorus apparently invented the term based on the model of the "Ostrogoths", but using the older name of the Vesi, one of the tribal names which the fifth-century poet Sidonius Apollinaris (1st cousin, 48 generations removed) had already used when referring to the Visigoths. The first part of the Ostrogoth name is related to the word "east", and Jordanes, the medieval writer, later clearly contrasted them in his Getica, stating that "Visigoths were the Goths of the western country." According to Wolfram, Cassiodorus created this east–west understanding of the Goths, which was a simplification and literary device, while political realities were more complex. Cassiodorus used the term "Goths" to refer only to the Ostrogoths, whom he served, and reserved the geographic reference "Visigoths" for the Gallo-Spanish Goths. The term "Visigoths" was later used by the Visigoths themselves in their communications with the Byzantine Empire, and was still in use in the 7th century.

Europe in 305 AD

Europe in 305 ADTwo older tribal names from outside the Roman empire are associated with Visigoths who formed within the empire. The first references to any Gothic tribes by Roman and Greek authors were in the third century, notably including the Thervingi, who were once referred to as Goths by Ammianus Marcellinus. Much less is known of the "Vesi" or "Visi", from whom the term "Visigoth" was derived. Before Sidonius Apollinaris, the Vesi were first mentioned in the Notitia Dignitatum, a late-4th-or early-5th-century list of Roman military forces. This list also contains the last mention of the "Thervingi" in a classical source.

Although he did not refer to the Vesi, Tervingi or Greuthungi, Jordanes identified the Visigothic kings from Alaric I (49th Lafón great-granduncle) to Alaric II (3rd cousin, 48 generations removed) as the successors of the fourth-century Thervingian king Athanaric (50th great-grandfather), and the Ostrogoth kings from Theoderic the Great (husband of 45th great-grandaunt) to Theodahad (nephew of husband, of 45th great-grandaunt) as the heirs of the Greuthungi king Ermanaric. Based on this, many scholars have traditionally treated the terms "Vesi" and "Tervingi" as referring to one distinct tribe, while the terms "Ostrogothi" and "Greuthungi" were used to refer to another.

Wolfram, who still recently defends the equation of Vesi with the Tervingi, argues that while primary sources occasionally list all four names (as in, for example, Gruthungi, Austrogothi, Tervingi, Visi), whenever they mention two different tribes, they always refer either to "the Vesi and the Ostrogothi" or to "the Tervingi and the Greuthungi", and they never pair them up in any other combination. In addition, Wolfram interprets the Notitia Dignitatum as equating the Vesi with the Tervingi in a reference to the years 388–391. On the other hand, another recent interpretation of the Notitia is that the two names, Vesi and Tervingi, are found in different places in the list, "a clear indication that we are dealing with two different army units, which must also presumably mean that they are, after all, perceived as two different peoples". Peter Heather has written that Wolfram's position is "entirely arguable, but so is the opposite".

Gutthiuda

GutthiudaWolfram believes that "Vesi" and "Ostrogothi" were terms each tribe used to boastfully describe itself and argues that "Tervingi" and "Greuthungi" were geographical identifiers each tribe used to describe the other. This would explain why the latter terms dropped out of use shortly after 400, when the Goths were displaced by the Hunnic invasions. Wolfram believes that the people Zosimus describes were those Tervingi who had remained behind after the Hunnic conquest. For the most part, all of the terms discriminating between different Gothic tribes gradually disappeared after they moved into the Roman Empire.

Many recent scholars, such as Peter Heather, have concluded that Visigothic group identity emerged only within the Roman Empire. Roger Collins also believes that the Visigothic identity emerged from the Gothic War of 376–382 when a collection of Tervingi, Greuthungi and other "barbarian" contingents banded together in multiethnic foederati (Wolfram's "federate armies") under Alaric I in the eastern Balkans, since they had become a multi ethnic group and could no longer claim to be exclusively Tervingian.

Other names for other Gothic divisions abounded. In 469, the Visigoths were called the "Alaric Goths". The Frankish Table of Nations, probably of Byzantine or Italian origin, referred to one of the two peoples as the Walagothi, meaning "Roman Goths" (from Germanic *walhaz, foreign). This probably refers to the Romanized Visigoths after their entry into Spain. Landolfus Sagax, writing in the 10th or 11th century, calls the Visigoths the Hypogothi.

Etymology of Tervingi and Vesi/Visigothi

The name Tervingi may mean "forest people", with the first part of the name related to Gothic triu, and English "tree". This is supported by evidence that geographic

descriptors were commonly used to distinguish people living north of the Black Sea both before and after Gothic settlement there, by evidence of forest-related names among the Tervingi, and by the lack of evidence for an earlier date for the name pair Tervingi–Greuthungi than the late third century. That the name Tervingi has pre-Pontic, possibly Scandinavian, origins still has support today.

The Visigoths are called Wesi or Wisi by Trebellius Pollio, Claudian and Sidonius Apollinaris. The word is Gothic for "good", implying the "good or worthy people", related to Gothic iusiza "better" and a reflex of Indo-European *wesu "good", akin to Welsh gwiw "excellent", Greek eus "good", Sanskrit vásu-ş "id.". Jordanes relates the tribe's name to a river, though this is probably a folk etymology or legend like his similar story about the Greuthung name.

Early origins

The Visigoths emerged from the Gothic tribes, probably a derivative name for the Gutones, a people believed to have their origins in Scandinavia and who migrated southeastwards into eastern Europe. Such understanding of their origins is largely the result of Gothic traditions and their true genesis as a people is as obscure as that of the Franks and Alamanni. The Visigoths spoke an eastern Germanic language that was distinct by the 4th century. Eventually the Gothic language died as a result of contact with other European people during the Middle Ages.

Long struggles between the neighboring Vandili and Lugii people with the Goths may have contributed to their earlier exodus into mainland Europe. The vast majority of them settled between the Oder and Vistula rivers until overpopulation (according to Gothic legends or tribal sagas) forced them to move south and east, where they settled just north of the Black Sea. However, this legend is not supported by archaeological evidence so its validity is disputable. Historian Malcolm Todd contends that while this large en masse migration is possible, the movement of Gothic peoples south-east was probably the result of warrior bands moving closer to the wealth of Ukraine and the cities of the Black Sea coast. Perhaps what is most notable about the Gothic people in this regard was that by the middle of the third century AD, they were "the most formidable military power beyond the lower Danube frontier".

Contact with Rome

Throughout the 3rd and 4th centuries there were numerous conflicts and exchanges of varying types between the Goths and their neighbors. After the Romans withdrew from the territory of Dacia, the local population was subjected to constant invasions by the migratory tribes, among the first being the Goths. In 238, the Goths invaded across the Danube into the Roman province of Moesia, pillaging and exacting payment through hostage taking. During the war with the Persians that year, Goths also appeared in the Roman armies of Gordian III (53rd great-grandfather). When subsidies to the Goths were stopped, the Goths organized and in 250 joined a major barbarian invasion led by the Germanic king, Kniva. Success on the battlefield against the Romans inspired additional invasions into the northern Balkans and deeper into Anatolia. Starting in approximately 255, the Goths added a new dimension to their attacks by taking to the sea and invading harbors which brought them into conflict with the Greeks as well. When the city of Pityus fell to the Goths in 256, the Goths were further emboldened. Sometime between 266 and 267, the Goths raided Greece but when they attempted to move into the Bosporus straits to attack Byzantium, they were repulsed. Along with other Germanic tribes, they attacked further into Anatolia, assaulting Crete and Cyprus on the way; shortly thereafter, they pillaged Troy and the temple of Artemis at Ephesus. Throughout the reign of emperor Constantine the Great (53rd great-granduncle), the Visigoths continued to conduct raids on Roman territory south of the Danube River. By 332, relations between the Goths and Romans were stabilized by a treaty but this was not to last.

War with Rome (376–382)

The Goths remained in Dacia until 376, when one of their leaders, Fritigern, appealed to the Roman emperor Valens (uncle of wife of 55th great-grandfather) to be allowed to settle with his people on the south bank of the Danube. Here, they hoped to find refuge from the Huns. Valens permitted this, as he saw in them "a splendid recruiting ground for his army". However, a famine broke out and Rome was unwilling to supply them with either the food they were promised or the land. Generally, the Goths were abused by the Romans, who began forcing the now starving Goths to trade away their children so as to stave off starvation. Open revolt ensued, leading to 6 years of plundering throughout the Balkans, the death of a Roman Emperor and a disastrous defeat of the Roman army.

The Battle of Adrianople in 378 was the decisive moment of the war. The Roman forces were slaughtered and the Emperor Valens was killed during the fighting. Precisely how Valens fell remains uncertain but Gothic legend tells of how the emperor was taken to a farmhouse, which was set on fire above his head, a tale made more popular by its symbolic representation of a heretical emperor receiving hell's torment. Many of Rome's leading officers and some of their most elite fighting men died during the battle which struck a major blow to Roman prestige and the Empire's military capabilities. Adrianople shocked the Roman world and eventually forced the Romans to negotiate with and settle the tribe within the empire's boundaries, a development with far-reaching consequences for the eventual fall of Rome. Fourth-century Roman soldier and historian Ammianus Marcellinus ended his chronology of Roman history with this battle.

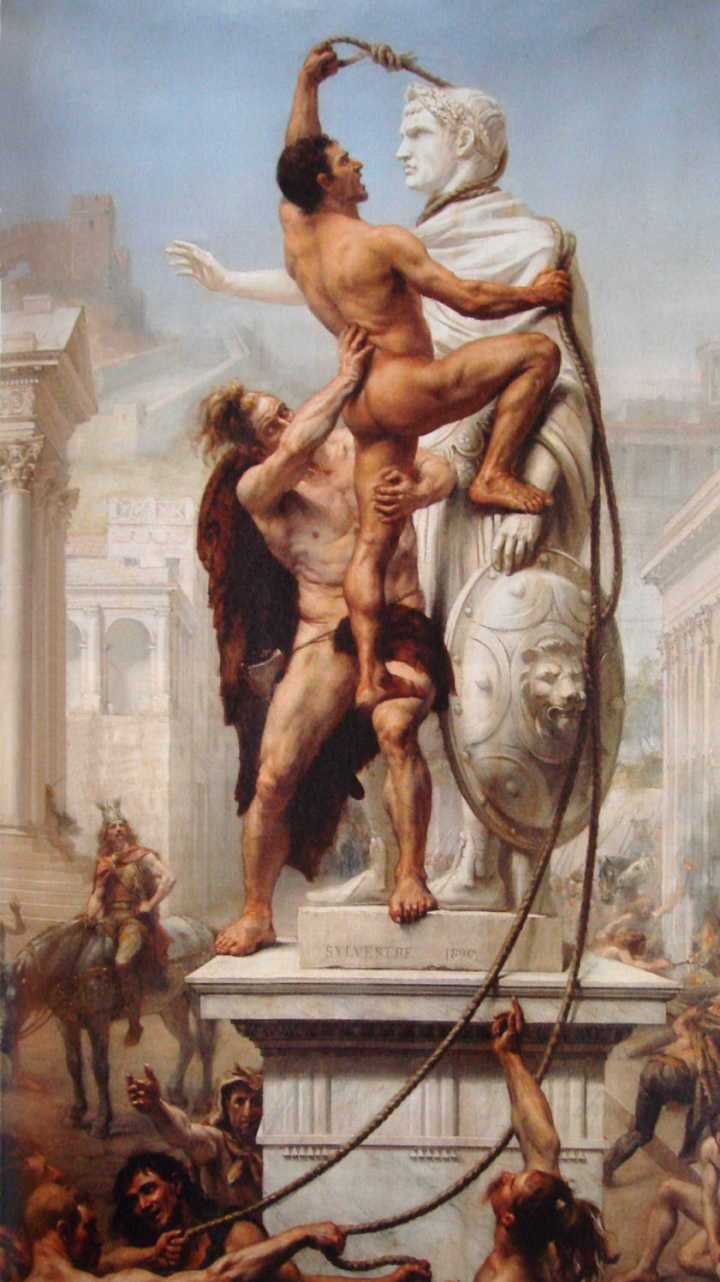

'Sack of Rome by the Visigoths on 24 August 410' by JN Sylvestre 1890

'Sack of Rome by the Visigoths on 24 August 410' by JN Sylvestre 1890Despite the severe consequences for Rome, Adrianople was not nearly as productive overall for the Visigoths and their gains were short-lived. Still confined to a small and relatively impoverished province of the Empire, another Roman army was being gathered against them, an army which also had amid its ranks other disaffected Goths. Intense campaigns against the Visigoths followed their victory at Adrianople for upwards of three years. Approach routes across the Danube provinces were effectively sealed off by concerted Roman efforts, and while there was no decisive victory to claim, it was essentially a Roman triumph ending in a treaty in 382. The treaty struck with the Goths was to be the first foedus on imperial Roman soil. It required these semi-autonomous Germanic tribes to raise troops for the Roman army in exchange for arable land and freedom from Roman legal structures within the Empire.

Reign of Alaric I

An illustration of Alaric entering Athens in 395

An illustration of Alaric entering Athens in 395The new emperor, Theodosius I (53rd great-grandfather), made peace with the rebels, and this peace held essentially unbroken until Theodosius died in 395. In that year, the Visigoths' most famous king, Alaric I, made a bid for the throne, but controversy and intrigue erupted between the East and West, as General Stilicho (husband of 51st great-grandaunt Serena Arcadia) tried to maintain his position in the empire. Theodosius was succeeded by his incompetent sons: Arcadius (52nd great-grandfather) in the east and Honorius (1st cousin, 49 generations removed), in the west. In 397, Alaric was named military commander of the eastern Illyrian prefecture by Arcadius.

Over the next 15 years, an uneasy peace was broken by occasional conflicts between Alaric and the powerful Germanic generals who commanded the Roman armies in the east and west, wielding the real power of the empire. Finally, after the western general Stilicho was executed by Honorius in 408 and the Roman legions massacred the families of thousands of barbarian soldiers who were trying to assimilate into the Roman empire, Alaric decided to march on Rome. After two defeats in Northern Italy and a siege of Rome ended by a negotiated pay-off, Alaric was cheated by another Roman faction. He resolved to cut the city off by capturing its port. On August 24, 410, however, Alaric's troops entered Rome through the Salarian Gate, and sacked the city. However, Rome, while still the official capital, was no longer the de facto seat of the government of the Western Roman Empire. From the late 370s up to 402, Milan was the seat of government, but after the siege of Milan the Imperial Court moved to Ravenna in 402. Honorius visited Rome often, and after his death in 423 the emperors resided mostly there. Rome's fall severely shook the Empire's confidence, especially in the West. Loaded with booty, Alaric and the Visigoths extracted as much as they could with the intention of leaving Italy from Basilicata to northern Africa. Alaric died before the disembarkation and was buried supposedly near the ruins of Crotone (next to present day Cosenza, Calabria), under the Busento River. He was succeeded by his wife's brother, Athaulf (49th great-grandfather of Raoul Ortiz Lafón).

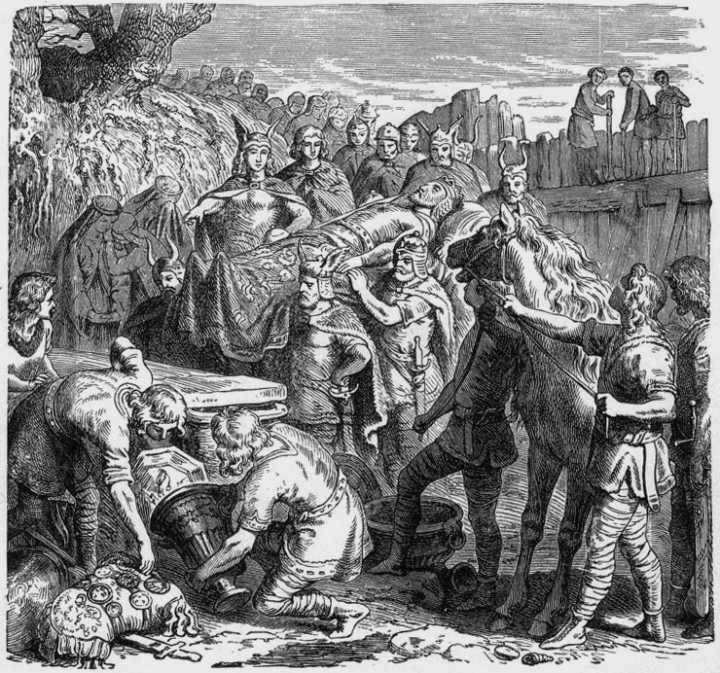

Death of Alaric; Visigoth tradition had their kings buried under diverted rivers to prevent graves being plundered.

Death of Alaric; Visigoth tradition had their kings buried under diverted rivers to prevent graves being plundered.Visigothic Kingdom

Europe at the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 AD

Europe at the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 ADThe Visigothic Kingdom was a Western European power in the 5th to 8th centuries, created first in Gaul, when the Romans lost their control of the western half of their empire and then in Hispania until 711. For a brief period, the Visigoths controlled the strongest kingdom in Western Europe. In response to the invasion of Roman Hispania of 409 by the Vandals, Alans and Suebi, Honorius, the emperor in the West, enlisted the aid of the Visigoths to regain control of the territory. From 408 to 410 the Visigoths caused so much damage to Rome and the immediate periphery that nearly a decade later, the provinces in and around the city were only able to contribute one-seventh of their previous tax shares.

In 418, Honorius rewarded his Visigothic federates by giving them land in Gallia Aquitania on which to settle after they had attacked the four tribes—Suebi, Asding and Siling Vandals, as well as Alans—who had crossed the Rhine near Mogontiacum (modern Mainz) the last day of 406 and eventually were invited into Spain by a Roman usurper in the autumn of 409 (the latter two tribes were devastated). This was probably done under hospitalitas, the rules for billeting army soldiers. The settlement formed the nucleus of the future Visigothic kingdom that would eventually expand across the Pyrenees and onto the Iberian peninsula. That Visigothic settlement proved paramount to Europe's future as had it not been for the Visigothic warriors who fought side by side with the Roman troops under general Flavius Aetius, it is perhaps possible that Attila (husband of 50th great-grandaunt Justa Gratia Honoria) would have seized control of Gaul, rather than the Romans being able to retain dominance.

The Visigoths' second great king, Euric (2nd cousin 49 generations removed), unified the various quarreling factions among the Visigoths and, in 475, concluded the peace treaty with the emperor Julius Nepos. In the treaty the emperor was called a friend (amicus) to the Visigoths, while requiring them to address him as lord (dominus). Though the emperor did not legally recognize Gothic sovereignty, according to some views under this treaty the Visigothic kingdom became an independent kingdom. Between 471 and 476, Euric captured most of southern Gaul. According to historian J. B. Bury, Euric was probably the "greatest of the Visigothic kings" for he managed to secure territorial gains denied to his predecessors and even acquired access to the Mediterranean Sea. At his death, the Visigoths were the most powerful of the successor states to the Western Roman Empire and were at the very height of their power. Not only had Euric secured significant territory, he and his son, Alaric II, who succeeded him, adopted Roman administrative and bureaucratic governance, including Rome's tax gathering policies and legal codes.

Greatest extent of the Visigothic kingdom of Toulouse in light and dark orange, c. 500. From 585 to 711 Visigothic Kingdom of Toledo in dark orange, green and white (Hispania)

Greatest extent of the Visigothic kingdom of Toulouse in light and dark orange, c. 500. From 585 to 711 Visigothic Kingdom of Toledo in dark orange, green and white (Hispania)At this point, the Visigoths were also the dominant power in the Iberian Peninsula, quickly crushing the Alans and forcing the Vandals into north Africa. By 500, the Visigothic Kingdom, centred at Toulouse, controlled Aquitania and Gallia Narbonensis and most of Hispania with the exception of the Kingdom of the Suebi in the northwest and small areas controlled by the Basques and Cantabrians. Any survey of western Europe taken during this moment would have led one to conclude that the very future of Europe itself "depended on the Visigoths". However, in 507, the Franks under Clovis I defeated the Visigoths in the Battle of Vouillé and wrested control of Aquitaine. King Alaric II was killed in battle. French national myths romanticize this moment as the time when a previously divided Gaul morphed into the united kingdom of Francia under Clovis.

Visigothic power throughout Gaul was not lost in its entirety due to the support from the powerful Ostrogothic king in Italy, Theodoric the Great, whose forces pushed Clovis I and his armies out of Visigothic territories. Theodoric the Great's assistance was not some expression of ethnic altruism, but formed part of his plan to extend his power across Spain and its associated lands.

After Alaric II's death, Visigothic nobles spirited his heir, the child-king Amalaric (4th cousin, 47 generations removed), first to Narbonne, which was the last Gothic outpost in Gaul, and further across the Pyrenees into Hispania. The center of Visigothic rule shifted first to Barcelona, then inland and south to Toledo. From 511 to 526, the Visigoths were ruled by Theoderic the Great of the Ostrogoths as de jure regent for the young Amalaric. Theodoric's death in 526, however, enabled the Visigoths to restore their royal line and re-partition the Visigothic kingdom through Amalaric, who incidentally, was more than just Alaric II's son; he was also the grandson of Theodoric the Great through his daughter Theodegotho. Amalaric reigned independently for five years. Following Amalaric's assassination in 531, another Ostrogothic ruler, Theudis took his place. For the next seventeen years, Theudis held the Visigothic throne.

Sometime in 549, the Visigoth Athanagild sought military assistance from Justinian I (husband of mother-in-law of 1st cousin 48x removed) and while this aide helped Athanagild win his wars, the Romans had much more in mind. Granada and southernmost Baetica were lost to representatives of the Byzantine Empire (to form the province of Spania) who had been invited in to help settle this Visigothic dynastic struggle, but who stayed on, as a hoped-for spearhead to a "Reconquest" of the far west envisaged by emperor Justinian I. Imperial Roman armies took advantage of Visigothic rivalries and established a government at Córdoba.

Visigothic Hispania and its regional divisions in 700, before the Muslim conquest

Visigothic Hispania and its regional divisions in 700, before the Muslim conquestThe last Arian Visigothic king, Liuvigild, conquered most of the northern regions (Cantabria) in 574, the Suevic kingdom in 584, and regained part of the southern areas lost to the Byzantines, which King Suintila recovered in 624. Suintila reigned until 631. Only one historical source was written between the years 625 through 711, which comes from Julian of Toledo and only deals with the years 672 and 673. Wamba was the king of the Visigoths from 672 to 680. During his reign, the Visigothic kingdom encompassed all of Hispania and part of southern Gaul known as Septimania. Wamba was succeeded by King Ervig, whose rule lasted until 687. Collins observes that "Ervig proclaimed Egica as his chosen successor" on 14 November 687. In 700, Egica's son Wittiza followed him on the throne according to the Chronica Regum Visigothorum.

The kingdom survived until 711, when King Roderic (Rodrigo) was killed while opposing an invasion from the south by the Umayyad Caliphate in the Battle of Guadalete. This marked the beginning of the Umayyad conquest of Hispania, when most of Spain came under Islamic rule in the early 8th century.

A Visigothic nobleman, Pelayo, is credited with beginning the Christian Reconquista of Iberia in 718, when he defeated the Umayyad forces in the Battle of Covadonga and established the Kingdom of Asturias in the northern part of the peninsula. According to Joseph F. O'Callaghan, the remnants of the Hispano-Gothic aristocracy still played an important role in the society of Hispania. At the end of Visigothic rule, the assimilation of Hispano-Romans and Visigoths was occurring at a fast pace. Their nobility had begun to think of themselves as constituting one people, the gens Gothorum or the Hispani. An unknown number of them fled and took refuge in Asturias or Septimania. In Asturias they supported Pelagius's uprising, and joining with the indigenous leaders, formed a new aristocracy. The population of the mountain region consisted of native Astures, Galicians, Cantabri, Basques and other groups unassimilated into Hispano-Gothic society. Other Visigoths who refused to adopt the Muslim faith or live under their rule, fled north to the kingdom of the Franks, and Visigoths played key roles in the empire of Charlemagne a few generations later. In the early years of the Emirate of Córdoba, a group of Visigoths who remained under Muslim dominance constituted the personal bodyguard of the Emir, al-Haras.

During their long reign in Spain, the Visigoths were responsible for the only new cities founded in Western Europe between the 5th and 8th centuries. It is certain (through contemporary Spanish accounts) that they founded four: Reccopolis, Victoriacum (modern Vitoria-Gasteiz, though perhaps Iruña-Veleia), Luceo and Olite. There is also a possible 5th city ascribed to them by a later Arabic source: Baiyara (perhaps modern Montoro). All of these cities were founded for military purposes and three of them in celebration of victory. Despite the fact that the Visigoths reigned in Spain for upwards of 250 years, there are few remnants of the Gothic language borrowed into Spanish. The Visigoths as heirs of the Roman empire lost their language and intermarried with the Hispano-Roman population of Spain.